Through the Eyes of Another

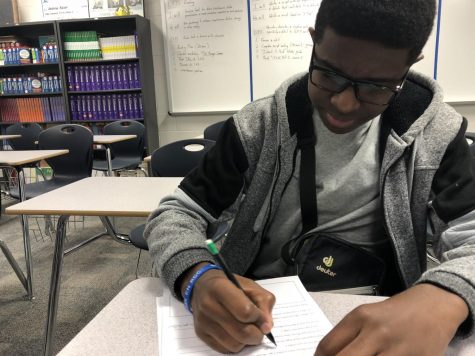

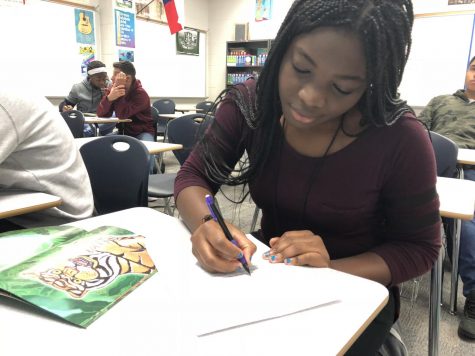

Marlene, Arlette, and Sylvain Muteba in AP Environmental Science with Mrs. Lamkin

There are over 100 languages, not including English, that cross the lips of students in Mansfield Independent School District every day. Students can walk down the halls and hear languages such as Spanish, Vietnamese, Arabic, Kurdish and Yoruba. Although these languages are common among Lake Ridge High School families, English is still the predominant language in the school. As such, students such as Marlene, Arlette, and Sylvain Muteba, who only speak French, have to deal with the complexities of the English language daily in order to learn and function in America.

The Mutebas come from the Democratic Republic of Congo, a large country in Central Africa. The move from a country nearly 8,000 miles away can cause a condition called Culture Shock, in which people, especially students, who have come from a different cultural environment, can feel confused and uncomfortable, according to and editorial by Robyn Tapley, and Assistant Professor of Counseling and Psychological Services in the Florida Institute of Technology.

“When you leave your home culture, you separate yourself from the people and circumstances that have defined your role in society. It is possible that you may experience a loss of some of your identity. The impact of this change can be disorienting and discomforting.” said Tapley.

Most migrants to the United States have nothing to work with, and must learn English either by immersion or by intense study. The Mutebas, however, have an advantage over the nearly 900,000 immigrants that come to the U.S. each year. The Mutebas rely each other in their classes in order to comprehend lessons which are taught to them in English, or they utilize teachers such as Marie Lamkin, who can speak both English and French fluently, and also helped in translating this interview for E.N.N.. But when times call for independent study, they are capable of working alone, but in the times they are allowed to work together, the siblings team up in order to pool their resources as well as their own knowledge in the English language.

Sylvain Muteba in his English Class.

“Sometimes we work together and sometimes we don’t, but when we work together we try to get along so we can understand more of the complicated words that are in the work we do.” said Sylvain Muteba.

With the Muteba’s recent move to the United States, the unique culture and people of the Democratic Republic of Congo is still fresh in their mind. The D.R.C.’s school system is oftentimes inferior to the United States in terms of government funding as well as the quality of education. Nearly 3.5 million children of primary school age are not in school, and 44% of students begin school late. The Mutebas claim that the D.R.C. is a lot harder on students than in America, and they also describe the people of the United States as more accepting towards strangers than those of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

“It’s a lot better for someone to be a stranger here than in the D.R.C., because people will go out of their way to help you here and try to make you feel welcome. The people here are a lot more comforting and the society itself is more comforting. The school system is also a lot easier here than in the D.R.C.” said Arlette Muteba.

Speaking a different language than that of their peers is a daily challenge for the Mutebas, either because of the language gap between them and their teachers or simply because of the complexity and speed of the conversations they have with their peers. While they do have plenty of resources, such as online translators as well as several teachers on campus who speak fluent French, there is still a struggle in the classes where their resources are limited or nonexistent.

“The hardest part of school for me is that I only understand half of what is said, either because I don’t know those words yet or they are talking too fast for me to comprehend. We do know a bit of English because we’re learning it at school, but we aren’t on the level of those who have spoken it their entire lives. We learn a few sentences and phrases every day, but when we speak in a conversation it doesn’t necessarily fit what we’ve learned, and when we do it’s often too fast.” said Arlette Muteba.

The Mutebas describe their experience coming to the school as welcoming and warm. The students at Lake Ridge High School, according to Marlene Muteba, treat them well and the staff do everything they can to help them succeed in school. However, sometimes people can get frustrated whenever they speak to them simply because the Mutebas cannot understand English sentences as fast as a fluent or native speaker would. They have to translate in their minds, and then translate it again into the English they know in order to have a conversation. They explain that they want people to know why they are delayed in reactions and responses to questions and statements.

“Even though we feel welcome at school and that people at least try to have a conversation with us, sometimes students in the U.S. speak too fast and they get frustrated when they finish a conversation and we’re still trying to comprehend the second sentence. If you approach us and speak slowly until we understand the first sentence, then you can move on to the next one. It’s not always possible, but it would help us better understand what you are saying.” said Marlene Muteba.

Lake Ridge High School is no stranger to foreign language. According to the Lake Ridge Counseling Center, 3% of students at Lake Ridge are in the E.L.L. program, which aids students in learning English while still honing their skills in their home language. While this is only the story of one group of siblings, these stories and struggles could apply to other students whose home language is not English.